“Where the spent lights quiver and gleam, . . .” Matthew Arnold, “The Foresaken Merman”

“ . . . — you can see / the whole sky pass through this head of mine, the mind is hatched and scored by clouds and weather—what is weather—when it’s all gone . . . .” Jorie Graham, “The Violinist At the Window, 1918” (from Sea Change, 2008)

A quality of suspense suffused Virginia Katz’s exhibition, “Transitory Nature,” at the Long Beach Museum of Art (now closed); and alongside the Museum’s curatorial and installation team, Katz deliberately emphasized it in the exhibition design and mounting of the exhibited works. Katz has frequently referred to herself as an artist whose focus is, above all, landscape—but her work continuously re-works and re-defines what is encompassed by the term. The conventional understanding of the term implies a singular prospect that, however sweeping, is usually more or less static. But for the last decade and more, Katz’s work has expanded the parameters of that definition, composing and recomposing landscape from within the landscape itself and through the elements that define it.

I became re-acquainted with Katz’s work a decade or so ago when I had an opportunity to see a group of paintings that were, once again, re-defining what landscape could be. Landscape or landscape elements were progressively built up over a support surface (panel or canvas or both) into what were essentially relief paintings. These were not simply a composition or arrangement of pigments, but what seemed like an appropriation of the terrain, of the earth itself. There is a long tradition of this kind of heavily impastoed landscape painting that probably begins in late 19th and early 20th century Expressionism, and continues right through Abstract Expressionism to more recent variations and practitioners (e.g., outstandingly, Kiefer). (Then, too, there are those artists for whom earth appropriated directly from a site is itself is a medium, e.g., Michelle Stuart.) In various iterations, these took on jewel-like metamorphoses (in some instances actually threading semi-precious materials through the pigments), becoming almost other-worldly. To build a slag heap out of a goldmine—isn’t that one definition of the human enterprise? This was not—could not—be viewed simply as landscape per se, but a kind of earth art, or land art.

I was not surprised to hear Katz speak of Robert Smithson and Andy Goldsworthy as influences. It’s almost impossible to look at these relief ‘landscapes’ and not think of Smithson; or more recent ‘interventions’ (as Katz would characterize her variously site- and non-site-specific assemblages) and not think of Goldsworthy. But a quick scan of her work for the past two decades makes it clear that she has been, in the largest sense, a ‘land’ or ‘earth’ artist from the start. Perhaps ‘Earth’ is the more accurate term, since her work has embraced both land and sea—from ocean waves and currents to the winds and the planetary atmosphere itself. Both nature and its transit have consistently been at the heart of her work. Also process and abstraction—and this is where ‘landscape’ becomes a useful term to describe her art: it starts from the artist’s perception—from a specific place and a certain perspective that may shift or be re-directed by forces within or outside the artist herself. I would also posit that data imaging—and increasingly as such technology has evolved (by way of NASA and Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory)—has further validated conceptual aspects of her work that appear very early in her career.

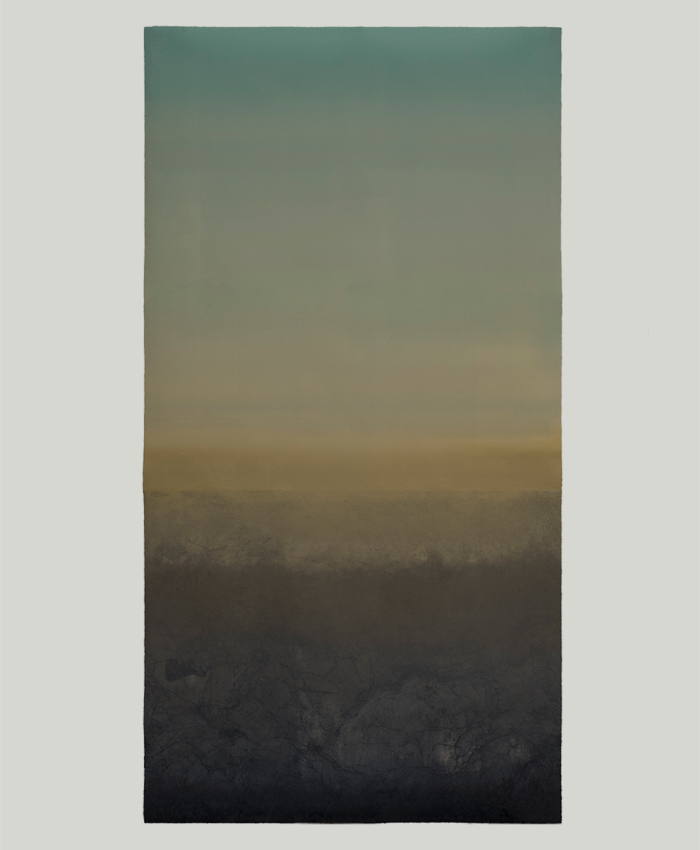

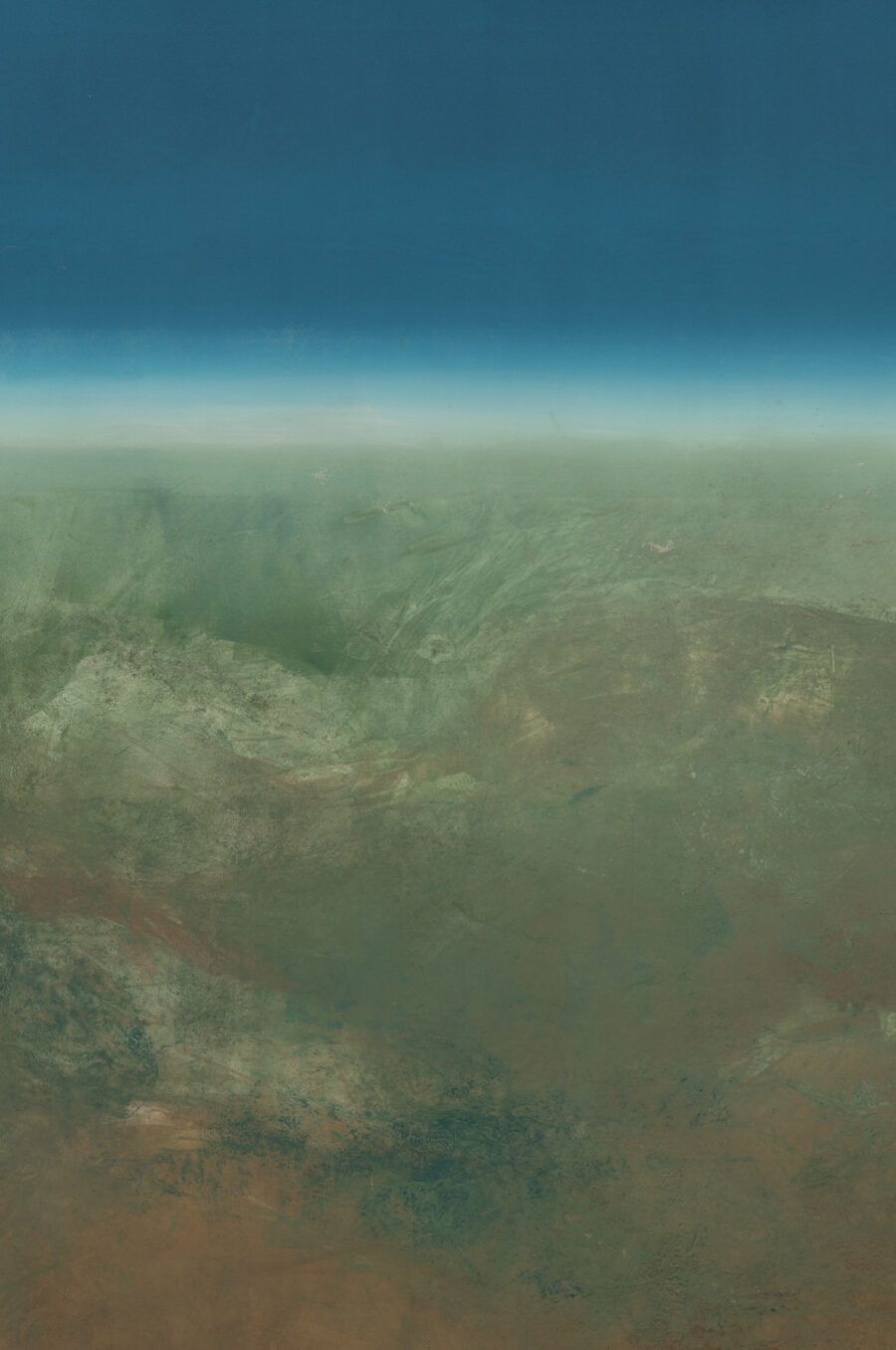

Katz, Expanse II, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Time is the element we feel most acutely walking through an exhibition like Transitory Nature—its simultaneously constant and continuous passage, and its suspension within the walls of the light-filled ground-floor galleries of the Long Beach Museum’s downtown satellite. The underlying propositions here, as in much of Katz’s art, are existential. We are both in and of nature, its product as well as its conceivable means of extinction and self-annihilation; and our views and understanding are limited by placement and perception, which shift and evolve over time (subject to whatever further ambiguities we might consider, pace Einstein, moving through the cosmos). A sense of these limits is at the heart of this exhibition, but also what is seemingly limitless, constantly variable within those physical limits—which is a sense of illumination and transformation. This is an experience that may be available randomly, casually on one level or another, at any moment of time or day. Katz’s means of capturing and crystallizing it are, essentially, light and color, structures found and improvised, both natural and man-made, and what she would call “interventions,” which, when you get right down to it, are really just an extension of earlier process-driven art that specified siting, placement, intervals. As in earlier work, she’s probing the notion of extension, but also its limits, more specifically the liminal zone between light and darkness.

We see this most explicitly, elaborately in the unique intaglio monoprints that map a complex terrain of light, shadow, depth and shallow, ‘ground’ and ‘surround’, emergence and submergence, projection and depression; the moving, shifting, floating horizon that can literally be anything and anywhere. Katz and the Long Beach Museum curatorial/installation team have emphasized this aspect by moving them away from the walls and (literally) hanging them from the ceiling at oblique angles to one another—so the viewer can weave through them, experiencing a sense of weaving, flux, floatation, contingency. (It sounds like it might induce vertigo, but it doesn’t.) Another aspect we might consider—practically a synonym—is simply uncertainty, and more specifically an uncertainty that engenders some degree of apprehension. Katz certainly has—Uncertainty (2022) is the title of one of the monoprints; and even within the serenity of this light-filled exhibition space, it set off quiet alarms. Reds are almost always the primaries of alarm—ignition, fire, lifeblood, labia and soft tissues, the most vivid blooms. But it’s also the burn itself—the deep, angst-laden psychological burn we’ve considered in work like Mark Rothko’s—to which contemporary artists continue to respond. Katz may herself be responding to its sustained declamatory force long spectral sustain here. But what once might have been an expression of private anguish is now externalized and almost immersive. Alarm and upheaval are keynotes in any news briefing; ‘days of rage’ are today any and every day of the week. We are in fact on the brink, at the edge of life and death; and our proximity may register at almost any moment, but we feel it particularly acutely at sunrise and sunset.

Reds are tamped down and variously modulated in Uncertainty, softened to an amber glow at the ‘horizon’ line and deepened into an almost blackened burnt sienna and still more complex browned-out zone at the very top, complicated by purple and blue undertones. Between this soft ‘ceiling’ and the lower ‘earth-bound’ quadrant of deep umbers and charcoals and browns shot through with pale umber and verdigris are various gradations of rose, sienna, and maroon. It’s both a ‘sunset’ as the familiar landscape cliché, and something more uncertain, even ominous—the sea of fire just over the horizon, with a promise of catastrophic destruction to come. The foreground itself offers an uncertain ‘landing’—less probable as ‘refuge’ than as sheer wasteland. (It’s a familiar scenario given the industrial wastelands that appear everywhere from the U.S. rust belt to China’s relentlessly overdeveloped landscapes.)

Katz pulls back from the sunset edge to works that appear inspired by aerial or satellite imagery of broad swaths of terrain and sky, simply titled Expanse. Expanse II (2020) first recalls views from ascending aircraft, as a plane might veer away from the temperate zones we presume support life like our own towards an arid terrain of mountains and deserts. Except—not exactly; and maybe not at all. We’re in a domain of free abstraction that complicates the existential angst of Uncertainty. Nothing is certain here, either. But we move in and out, through waves and eddies and prominences and depressions, overpainting and backwashes that give us a ‘landscape’ we’ve never actually seen in the real world. The lower quadrant seems less sedimentary than Uncertainty’s, less an accumulation than an accretion of disturbances—not a ‘desert’, but a duststorm. Yet nothing here is entirely implausible. The bright white ‘horizon’ line beneath an azure gradient might suggest the earth’s (or a coastal) edge, the light following the curve. But in a more straightforward sense, we’re staring straight into (not across) a mesmerizing void, the unknown—the ‘unknown unknowns’ (unlike the deep blue of the distant atmosphere pressing toward the ionosphere), to give it a Rumsfeld spin.

It’s beautiful and it’s terrifying and we’re still making it up as we go along. It’s an ‘expanse’ that expresses not simply a landscape, but a phenomenon, a way of seeing. We’re still learning how to see and narrate it, and so much is lost in the dust, smoke, and haze of it all. (I sometimes think that for all the technological advancement and all the millions of human minds and digits scraping wholesale the databases of civilization up to the present moment for so-called large language/data model AI programs, Silicon Valley is still (and just barely) the high-tech version of Hollywood—where the most foundational postulate is that “nobody knows anything.”)

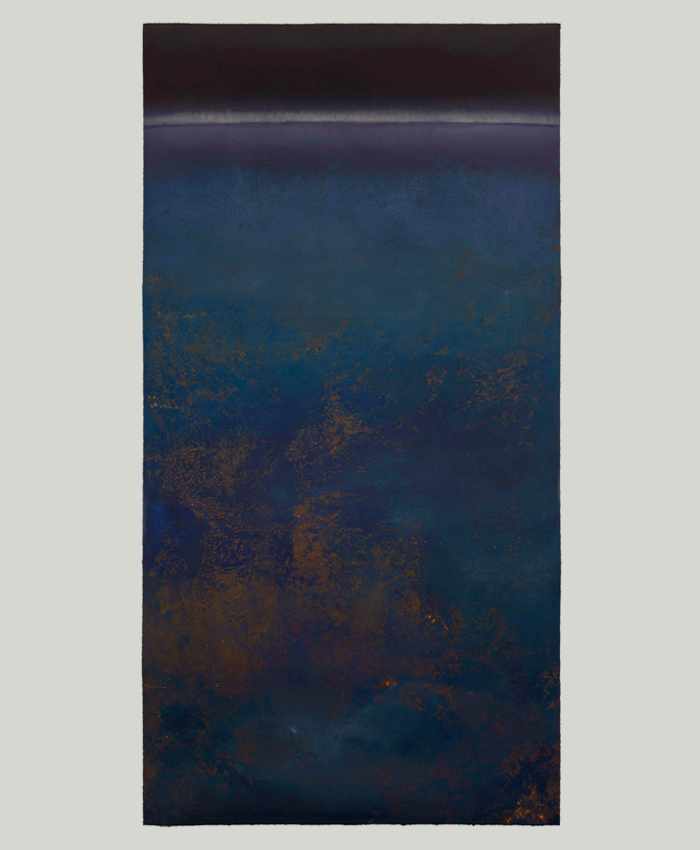

Katz, Unrest, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Unrest (2020) references satellite imagery of the billion or so ‘points of light’ that indicate significant human settlement or development across the planet—and the energy consumed to make them visible from space. Here the eye moves in two directions, towards both the top and bottom quadrants of the rectangular print, with the pale white horizon line becoming the planet’s sunlit edge against the blackness of space, and pale red-orange flecks scattered through a soft grey kidney-shaped nimbus or archipelago signaling the energy disturbances given off by conceivably living inhabitants. The print creates its own abstract terrain—something we might read as variously mist-enshrouded, arboreal, volcanic, mountainous; but we’re also aware of the extent the ‘disturbance’, the ‘unrest’ is part of it. Those ‘points of light’ are part of this ‘natural’ landscape, as integral as any other element. The sense of distance and darkness or keynotes here. Reflection does not always come easily in the clear light of day, when the unrest, the constant churn and upheaval of animal activity is all around us.

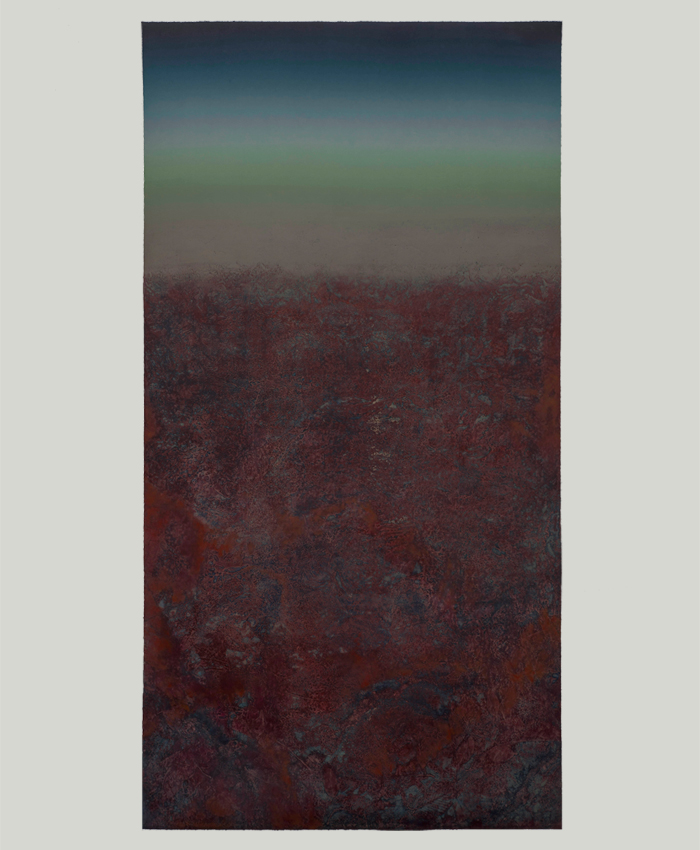

Katz, Australia – Continental Burn, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

In Australia – Continental Burn (2020), Katz directly references Australia’s long history of uncontrolled (almost uncontrollable) bushfires and wildfires in areas of urban/suburban and bush/outback interface. Records of such wildfires (also astonishingly high atmospheric temperatures) go back as far as the mid-19th century—making the continent a kind of leading indicator as to where uncontrolled human activity and climate change might take us. (Australia’s bushfires of 1974-75 all but incinerated vegetation across almost 15 percent of the continent—before climate change was even a major preoccupation of environmental scientists; and the situation hasn’t improved much over the decades leading into this century.) Here, Uncertainty’s sunset reds have literally bled into the ‘terrain’. The only suggestion of green—really the palest turquoise occurs on a gradient in the upper quadrant of the print. In the lower two-thirds of the print there is only blood red surfacing over a sediment of purple, mauve and amethyst mottled grays and blacks—the ‘bruised’ terrain beneath the open wounds at its surface. Human imagination generally goes to sites of military urban immolation (Hiroshima) or systematic mass murder (the systematic genocide of the Holocaust, Cambodian killing fields, etc.); but we’re reminded here that ‘killing fields’ encompass entire continents (or in recent years, oceans—as impossibly overheated waters off the coast of Florida this summer destroy the coral reefs that were once a frontline of coastal protection). By now it’s clear to most of us that the Sixth Extinction is already under way (and literally under our feet), and Katz is channeling its carnage in these unique prints.

It’s not all fire and brimstone (or smoke and ashes) in these monoprints. As her palette of inks and paints shifts toward the cooler end of the spectrum, Katz offers a more serene, almost tranquil perspective on nature’s ‘transitions’ (though the titles of these works (2020-2022) readily convey their underlying fatalism—e.g., Slipping Away, On the Brink, Omen). Always Katz reminds us of the juxtaposition of perspectives: our placement, vantage point, perceptions, apprehensions, versus the conceivable geophysical actuality of a planetary surface, heat, friction, gravity, reactivity, movement, circulation, nature, the life around us (and its end), entropy. The ‘end’ (which is always a ‘beginning’) is beautiful, too. (Okay, so I’m human—apologies for that.)

As is fairly clear from the unique intaglio monoprints—which are worked over with various materials conventional and unconventional (e.g., aluminum foil, natural and synthetic materials), inks and hand-painting and drawing in pigments and pencils, Katz is continually experimenting—as she has since the very beginnings of her career; and like artists since the turn of the last century, she is prepared to use whatever is at hand—or (not surprisingly) under foot. “Beauty’s where you find it,” said somebody once. It takes an artist to know what to do with and make of it. This can be anything from desiccated leaves and brush, lost petals or decaying foliage, or stuff that goes straight from our bags or toilet racks into the garbage. Or the facial tissue that just left your cheek or nose. Again, as with her larger works—work more easily recognized as ‘landscape’ or encompassed by the term—the other works here are as much about seeing and the way we see and how our imaginations are engaged by perception, however fleeting or ephemeral—what might be glimpsed, almost literally, in the blink of an eye. In a series of tiny watercolors, executed on squares of facial tissue, the dominant color frequently registers first, almost as if caught within a flash of light (the ‘blink of an eye’). The flash or flicker is the starting point. A larger impression or color modulation unfolds out of what might be a kind of stain catching the folds, wrinkles and textural imperfections of the material. We might read a ‘horizon line’ in Disposition (2022), but this is only the starting point of what could be a tiny dream fragment—a marsh, an imaginary ruin, shadows contained within shadows, with indigo and watery blues above and below.

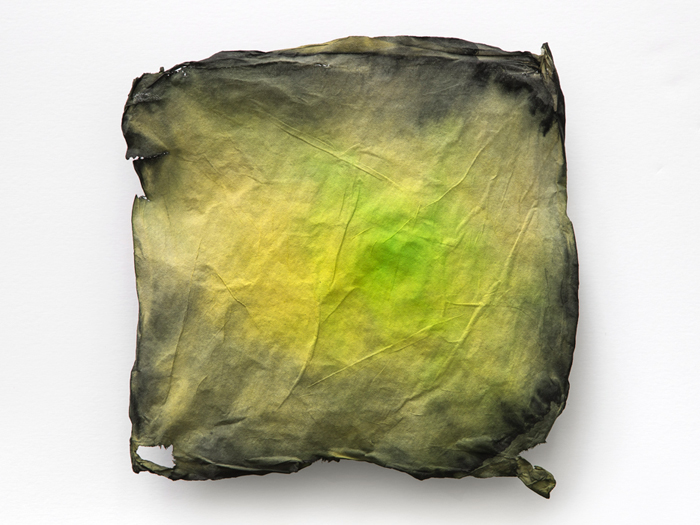

Katz, Singed, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

Katz has a fascination for the material simply as a medium for color—its simultaneous capacity for diffusion and intensification; but she’s taken the fascination to another level to build an analogue to the fragile material itself: the ephemeral but unforgettable fragment. It’s that world disclosed within the blink of an eye, instantly forgotten or discarded, only to be recovered and revered in all its talismanic potency: a patch of true green lost in a pale meadow framed by torn, blackened edges (Singed, 2022); a smouldering blaze of light folded between velvety dark blacks closing in on it (Last Light, 2022); a harmony (or counterpoint?) of greens that leave the tissue fragment in shreds Katz titles ironically A Vision of Completeness (2022). Yet that is exactly what it is. The idea, thing, vision is consumed, consummated; and there’s nothing else left. That’s life—if we’re lucky.

Katz, Last Light, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

Katz’s Interventions return us full circle both to her conceptual foundations and her intense, immersive engagements with landscape painting which had some of the qualities of earth or land art. Yet her focus here is not far from the ephemeral, cast-off quality of her fragile Watercolors—the casual, fleeting encounter or engagement that is somehow sustained over an interval of time. We find this sort of thing anywhere and everywhere—from private wooded properties and tranquil leafy neighborhoods, to forlorn carparks, scarred post-industrial city blocks, and the grittiest of urban wastescapes. Nature seems to have its own artifice; and in L.A., it’s frequently that random, scrappy bougainvillea torn this way and that that simply won’t die. It’s a gritty green interface that inspires Katz to return the favor with the artifice of her own tools and synthetic pigments.

The balance is fragile and the installation makes this evident—in “Transitory Nature,” the “interventions” are set into the brick walls of the Long Beach Museum’s downtown galleries. Unstable (2021) is a tangle of commingled painted wire and found tree branches supporting a nest with eggshells painted in gouache. The precarity could not be more explicit. Devolved Anatomy (2023) is a kind of curve of intersecting branches, the lower of which (in painted wire) drags a loose piece of fencing. ‘Nature’ may or may not be ‘winning’—but it’s not as if death is ever very far away. Then on an actual piece of fencing set into the brick, a cascade of rosy pink, fuchsia, and pale pink blossoms (in paint) seems almost celebratory, while giving the lie to it all.

Katz, The Nature of Things, 2022-23. Courtesy of the artist.

Taken in its entirety, “Transitory Nature” had a tremendous luminosity. The work fairly glowed in the Long Beach Museum’s sunlit downtown galleries. Still its dark, fatalistic undercurrent made itself felt both within and beyond the visible spectrum. Katz’s titles for some of the works might be taken as signposts, but the viewer scarcely needed a precise mapping of the chromatic, phenomenological or epistemological terrain. There is what we see and what we know, what happens in between, and what we can neither see nor know (at least with any degree of certainty or comprehension)—which, AI notwithstanding, seems to dwarf the first category. Nature, life—we sometimes try to tell ourselves—has a way of pushing back and pushing through. But the physics of our planet and universe are unforgiving; and there have been many successive warming and cooling geologic phases of this planet and biosphere that killed off massive numbers of us (meaning all indigenous earthly life forms). Glaciers and volcanoes once ripped open and scarified the surface of the planet. Now humans do, as they have for the last few centuries. But Katz isn’t simply abstracting our ant farm of extraction into a succession of aerial anthill views. Nature’s transitions are never simply uni-directional—nor are our own, even viewed simply within a social context. (Katz’s Interventions are a conceptually audacious demonstration of this.)

Horizon lines measure out the time of most creatures inhabiting the land, yet our two-legged breed continues to press relentlessly beyond them. We see and know more than ever before in human history. But there’s no telling which of our fleeting illuminations will survive our star’s death. Most of the fire and light driving us forward (and back) are on loan. Katz’s haunting Long Beach Museum exhibition puts forward the modest proposal that our species pay it forward with interest.